Originally Published: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/checklists-aviation-cybersecurity-edward-frye/

In my previous article, we discussed how some of the aviation and cyber security regulations have come about, and what are some of the driving factors. Typically it is a loss of some sort; most of the aviation regulations are borne of the loss of life. The pre-flight checklist is no exception.

In the 1930s, the aircraft that would become the B-17 flying fortress crashed during one of the initial test flights. In the post-crash investigation, it was quickly determined that the elevator control lock was not removed causing the aircraft to stall. Boeing came up with a simple solution to prevent such tragedies from happening in the future, the checklist. This list displayed the critical items a crew must do before takeoff in a sequential way, thus avoiding any pilot to ever have to rely on his memory.

A checklist is a type of job aid used to reduce failure by compensating for potential limits of human memory and attention. It helps to ensure consistency and completeness in carrying out a task or series of tasks. Checklists are used in many different industries for all sorts of purposes. It may be as simple as a “to-do” list, a schedule or a series of items to perform.

Checklists are not how-to guides.

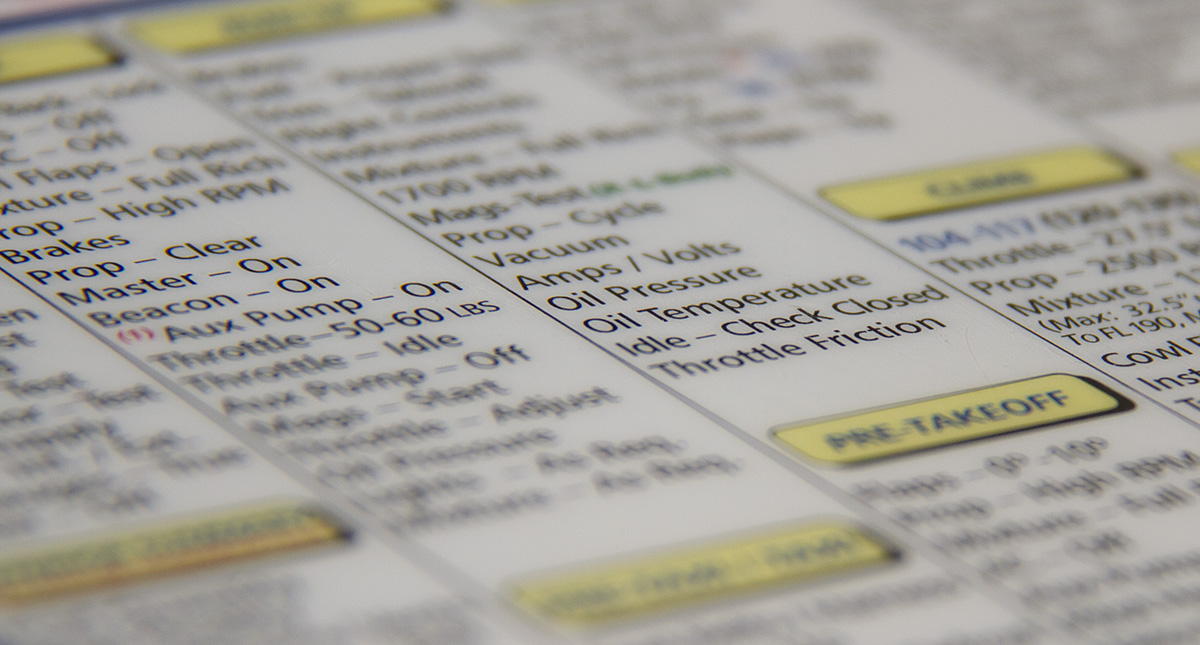

In aviation, there are two types of checklists that a pilot must use to ensure the safe and successful outcome of a flight. There is the “read-do” / “do-verify” objective checklist for each of the phases of the flight, these include the pre-flight checklist, the engine-start, taxi, engine run-up, normal takeoff, climb, cruise, descent, and after-landing, and securing checklists. These are short lists of items to check or set and touch on the most critical items that are often missed at those stages of flight.

This article isn’t about the prescriptive checklists nor the prescriptive controls in cyber security. In addition to those checklists which are prescriptive, there are other checklists that are much more subjective. For instance, there are checklists you can use to assess the risk of making a flight. The PAVE checklist, or “Pilot, Airplane, enVironment, External factors”, has another checklist within it, the “I’M SAFE” checklist which expands to “Illness, Medication, Stress, Alcohol, Fatigue, and Emotion/Eating”. These checklists are used to help you make a go/no-go decision about proceeding with the flight. A portion of these checklists are extremely prescriptive. For example: no alcohol in the previous 8 hours, no more than 0.04% BAC; but within that same IMSAFE checklist, there is Fatigue and Emotions which are personally subjective.

You may be wondering how this relates to cybersecurity. The cybersecurity frameworks such as ISO27001, are essentially checklists. They are not “How-To” instructions. They require a subjective interpretation to properly implement. They touch on areas of concern that are often missed or overlooked that if mishandled can create great loss for an organization.

Within the 27001 framework, the first step is “Understanding the Context of the Organization”. You cannot implement a proper security program without first understanding what the business does, who is interested in the company and its security program, what is the scope, what are internal and external factors that can contribute to the context of the organization, and so on.

Then the next step is to work with the leadership team, the executives, or the board to ensure the objectives of the cybersecurity program are established. The framework builds upon each step to establish the cybersecurity program or Information Security Management System as the framework calls it. When performing each step, you need to keep in mind the first step, the context of the organization, the internal and external factors.

When I reevaluate the company as part of the annual risk assessment and review process, or approach a new cybersecurity role, I go back and start the checklist over and will re-interview the key stakeholders, ensuring that my understanding of the context of the organization, those internal and external factors, is valid.

But I want to go beyond my own use of checklists in cybersecurity. Checklists can be used to allow teams to make authoritative decisions and get things done when my team or I are not around. This type of discipline would come into play in establishing an application security program into a software development process that involves “Continuous Integration and Continuous Deployment” (CI/CD). Of course, as is stated in the book “The Checklist Manifesto - How to get things right, by Atul Gawande”:

Just ticking boxes is not the ultimate goal. Embracing a culture of teamwork and discipline is.

Following checklists and ticking boxes is not the goal. What we are trying to reduce the risk to the organization, the employees, the customers, the data. And we are trying to embrace a culture of teamwork and discipline.

Checkbox security, or security that focuses strictly on compliance to a standard, does not make your environment secure. It is a strategy that may eventually lead to failure due to complacency. Some have argued that following a standard means that you are “secure”. Compliance with these standards simply means that you are aligned with a set of criteria with the goal of protecting sensitive data.

Some checklists need to be practiced. Going back to aviation, there are some procedures which must be muscle memory -- complex issues that require skills at the ready. For example, multi-engine aircraft have a unique engine-failure characteristic, which if not corrected immediately, is almost never recoverable. In the next article, I will discuss “the-drill” and practicing other procedures in aviation and cybersecurity.

- Log in to post comments